Birdcage piano: are they functional instruments?

The article analyzes birdcage pianos, a visually attractive type of musical instrument but with fundamental design flaws such as a low-quality scale and an inefficient damping system. These flaws make maintenance and tuning of birdcage pianos difficult and often lead technicians to refuse to work on these instruments. Additionally, the article compares the characteristics of birdcage pianos with those of vertical and grand pianos, emphasizing the importance of the position of the dampers in achieving greater efficiency in damping the impact node.

According to this technician's biased view, birdcage pianos belong in the category of exotic furniture, along with square pianos and other peculiarities dear to interior decorators' hearts. As musical instruments, they fall short of even reasonable expectations, and I refuse to work on them.

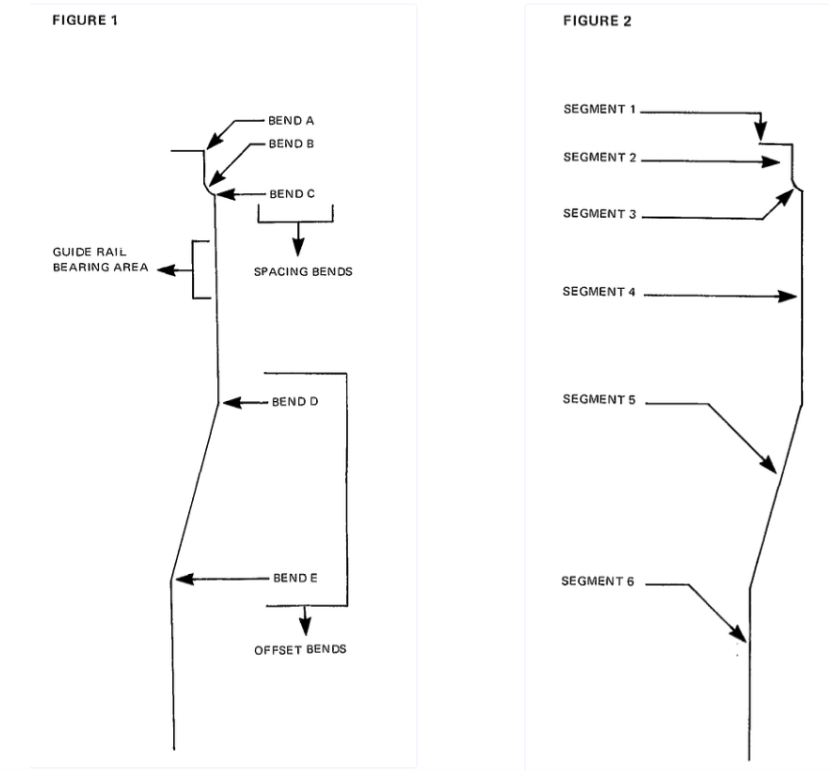

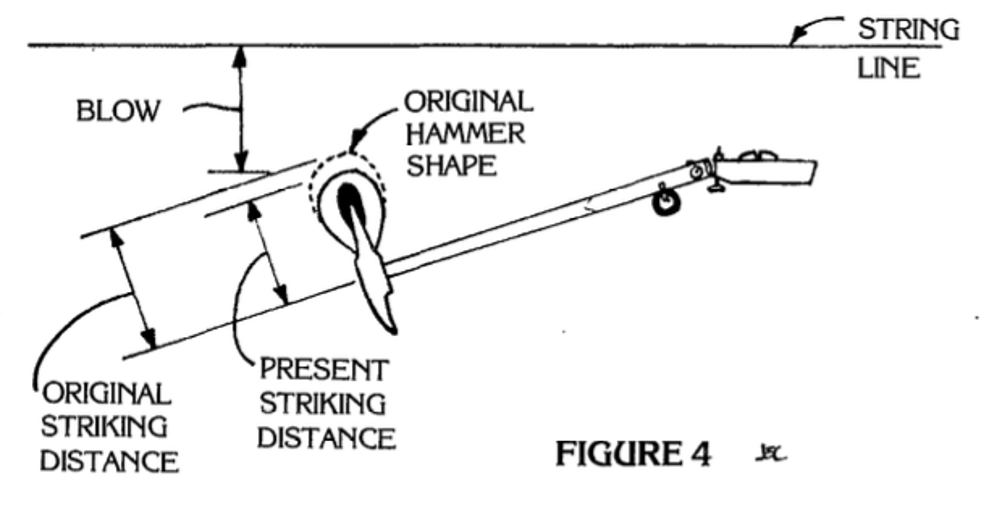

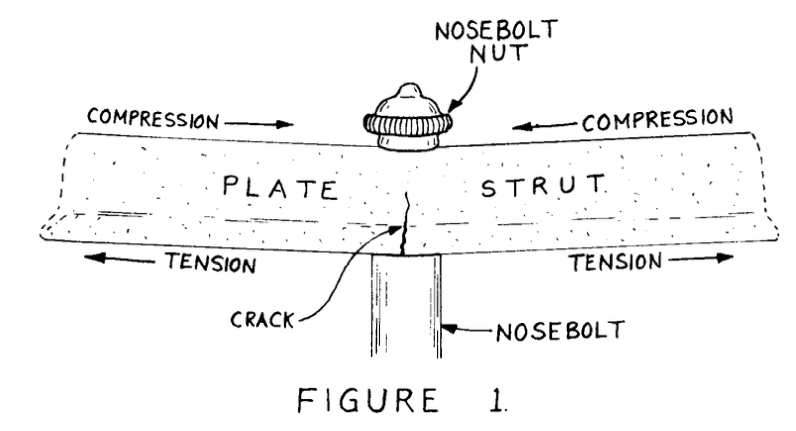

These pianos have two fundamental design flaws: a poor scale and an inefficient damper system. The most primitive aspect of scaling is that they are not overstrung. Every birdcage I have seen has all strings on one bridge running straight up and down. This results in a drastically foreshortened scale with all its accompanying tuning difficulties, as well as too many bridge pins crammed into too small a space, especially in the middle. Bridge problems are inevitable in this design.

The damper system is the most troublesome for the tuner. With the rail mounted above the hammers, placing a strip mute in place is almost impossible. The tuner must either mute below the keybed and use a short tuning tip to clear the damper rail or remove the damper rail altogether and tune without dampers. In either case, it can be a real hassle.

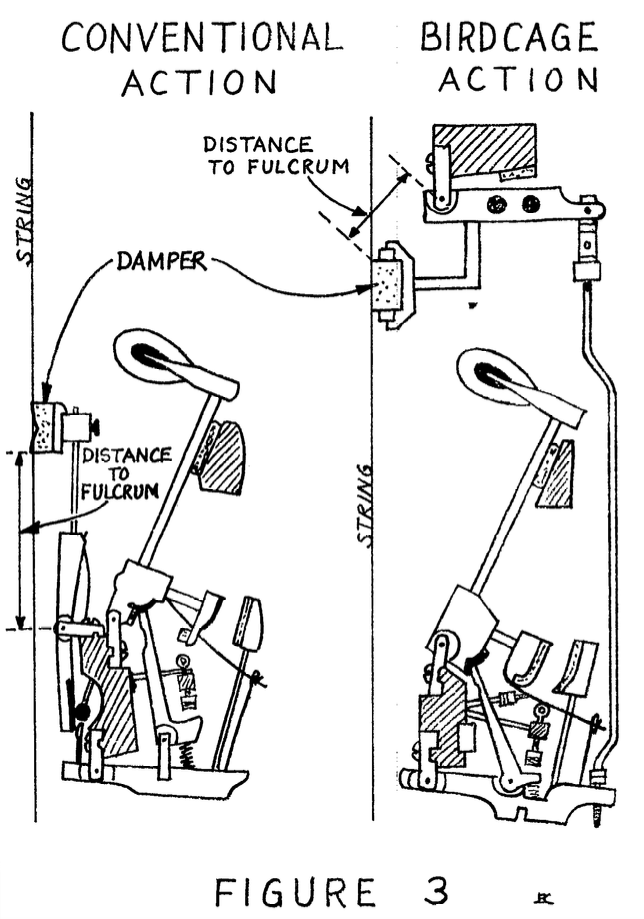

William Braid White once remarked that the upright piano has an inherent advantage over the grand piano in that the pinblock of the former can be solidly glued into the framing of the instrument, while that of the latter must be suspended over the action, supported mainly by the plate and the rim at the very ends. His point is well taken, but I submit that any advantage in that area is more than offset by the fact that the dampers in a grand piano can damp the strike-point node, while those of an upright cannot. Since the dampers are on the same side of the strings as the hammers, they must necessarily be placed above or below the strike point.

Given this choice, the dampers are more efficient if placed below the hammers. However, in the birdcage piano, they are above. Dampers can be assisted by springs or weights, and springs tend to work better because they cause the damper to follow the string more closely than bouncing inertia-laden weights. Modern upright pianos use springs, but the birdcage relies on weights.

The thickness of felt used is much more critical in a birdcage than in a conventional upright piano, as I learned to my dismay on one occasion. The fulcrum in the birdcage action is so close to the felt, as compared to the conventional action (see Figure 3), that regulation becomes difficult. For the top of the felt to clear the strings, the bottom must move quite a distance, yet the entire felt surface must make contact when the damper arm is as horizontal as possible; otherwise, the damper won't do its job.

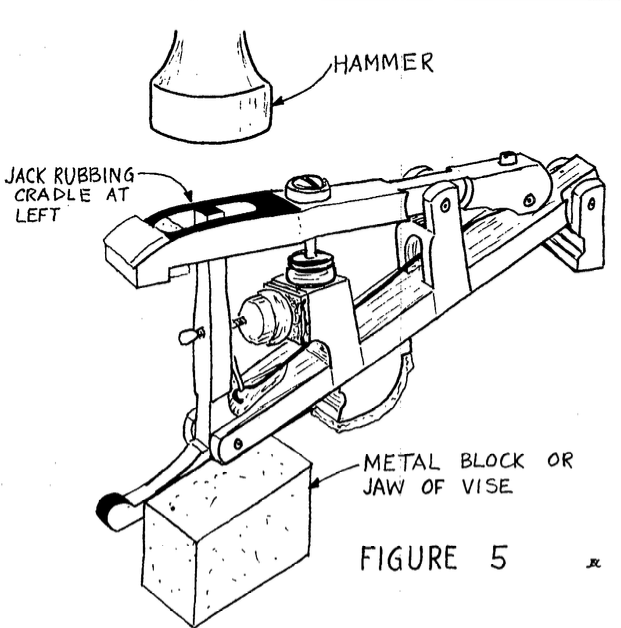

Parts availability presents a real challenge. While some parts may be adaptable, that takes time, and time is money. For example, let's say you want to install a new set of hammers. An ordinary set won't work because the moldings will be shorter in the bass to allow for overstringing. So, even if the technician has a jig set up to align the hammers on a straight line, they still must solve the problem of the short molding length. Standard hammershanks could probably be used, as well as bridle tapes and regulating screws, but little else.

Last summer at the convention in Cincinnati, someone stopped me in the hallway to ask about the possibility of replacing a birdcage action with one of modern design. "Could it be done," he wanted to know, "if cost were no object?" Well, yes, it can be done, but the cost would be considerable. Any reputable action manufacturer could do it if given a scale stick and other critical dimensions, but the first one of anything is going to be far more expensive than the ten thousandth. There would be a lot of work involved in fitting the action to the piano, too, because the birdcage uses wooden action brackets. Even if such a replacement action were available, you couldn't just set it in, tighten four thumb nuts, and tune it. Servicing a birdcage usually involves a certain amount of patchwork and questionable on-the-spot repair work, rather than the kind of work that involves an established procedure and a written guarantee. If the technician charges for what their time is genuinely worth, they might feel a twinge of conscience because the fee isn't justified by the results. On the other hand, if they set their fee based on the results, they could starve working on a birdcage.

What's Your Reaction?