The Invention of the Sostenuto Pedal

This article explores the history of the sostenuto pedal, which sustains specific notes while allowing the dampers of others to continue functioning. While some credit the invention to Albert Steinway, the Boisselot brothers of France received the patent for the sostenuto pedal in 1843 or 1844. However, the pedal was not pursued for long by the Boisselots, and others like Claude Montal and Zachariae developed different mechanisms for it. In 1874, Waldo Hanchett filed a patent for an improvement in piano-forte attachments, and Steinway filed their patent a few days later, which was approved in less than two weeks. A patent dispute ensued, and during their defense, the Steinway brothers found evidence of Montal's earlier exhibition in 1855, proving that Hanchett was not the true inventor of the sostenuto. Meanwhile, Albert Steinway committed himself to improving his design and received patents for grand, vertical, and square pianos in 1875.

Who was the inventor of the sostenuto pedal?

This question has been asked many times, and there are various answers that have been given. Some people believe that Albert Steinway was the inventor, citing his patents from 1874-75. Others give credit to Claude Montal, a French piano maker who was also known for his book on piano tuning and repair, which was first published in 1836. Montal was blind himself and initiated the first training program for the blind in Paris in the 1830s. Those are the two most commonly cited answers, but neither of them actually invented the third pedal in the middle that hardly anyone uses, but that seems to be a requirement for every self-respecting grand piano.

The credit (or blame, depending on your point of view) for the invention of the sostenuto pedal actually belongs to the Boisselot brothers, who were piano makers from Marseilles in southern France. They invented this pedal during a time when many pianos already had four to seven pedals for various purposes, such as changing the tone by putting strips of leather between the hammers and the strings, operating drums and bells, laying parchment on the strings to produce a “bassoon-like” sound, etc. It was a time of constant experimentation and change in the world of pianos when the square piano began to be displaced by the upright, and the action of the grand was transforming from a simple jack attached to each key to the double-escapement action in use today.

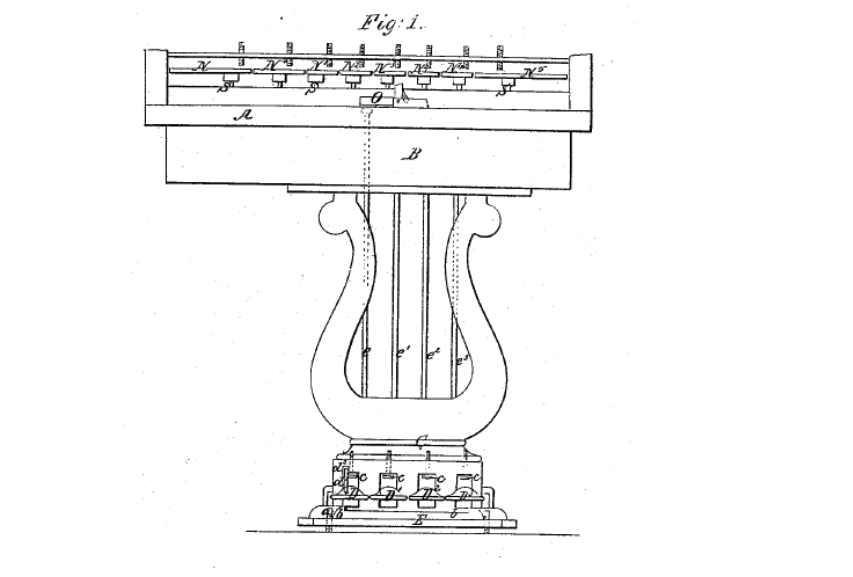

The Boisselot brothers received their patent for the sostenuto in 1843 or 1844. This was not their only patent at that time; they also patented a different pedal that received more attention. This particular pedal allowed one to play octaves by pressing one key, making it possible for amateurs to imitate the passagework in octaves of the virtuosos of the time. Both the octave pedal and the sostenuto were displayed at the Paris Exposition of 1844. A reporter wrote about them in detail in the June 30, 1844 edition of Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris, a weekly newspaper covering everything related to music, including the latest concerts by Liszt.

The reporter, G. E. Anders, described with enthusiasm the possibilities of the octave pedal. It included, in fact, two different mechanisms. The first involved shifting the hammers and keyboard. Each note had five strings instead of three, but three were tuned to the standard pitch, and two of them were tuned an octave lower. In rest position, the three standard strings would be struck, while in shift position, the strings an octave lower would be struck along with standard strings, creating the sound of an octave. A second mechanism consisted of an intermediate lever that connected the key to the hammer an octave higher and/or an octave lower at the same time. As the reporter enthused, when using both methods simultaneously, this meant one could play four keys in one hand and have sixty notes sound at once. Doing the same with both hands would mean one hundred and twenty notes at once!

However, the journalist was more optimistic about the other new pedal, called "à sons soutenus à volonté" (sustaining tones at will), regarding its musical potential. According to him, this pedal could hold one or multiple dampers up as long as the pedal was pressed, while the other pedals functioned as usual. Although it is not clear from the description exactly how the mechanism was designed, an escapement lever and a rocker were mentioned as holding the individual dampers up. The journalist was amazed to see such a simple mechanism serving a useful function and wondered why nobody had thought of it earlier. Unfortunately, I have been unable to access the patent drawings so far.

It appears that neither of these pedals was pursued for very long by the Boisselots, and they seem to have abandoned the sostenuto patent. This is because it was necessary to pay an annual fee in France to keep a patent current and in effect. However, in 1855, Claude Montal exhibited pianos, both grand and upright, with a pedal called "à sons prolongés" (his own version of the Boisselots’ term) that had precisely the same function. According to his biography published in 1857, he had first created this pedal in 1844 and had later improved it. Montal had also displayed pianos at the 1844 exposition and undoubtedly saw and heard about the Boisselots' pianos. He was more persistent in his pursuit of this idea, exhibiting pianos with this feature again at the London exposition of 1862, although his main focus was on another pedal he had invented, the expression pedal. This pedal moved the hammers closer to the strings while compensating in the keys and action, so no lost motion was introduced. Unfortunately, Montal died in 1865, and the French version of the sostenuto seems to have died with him.

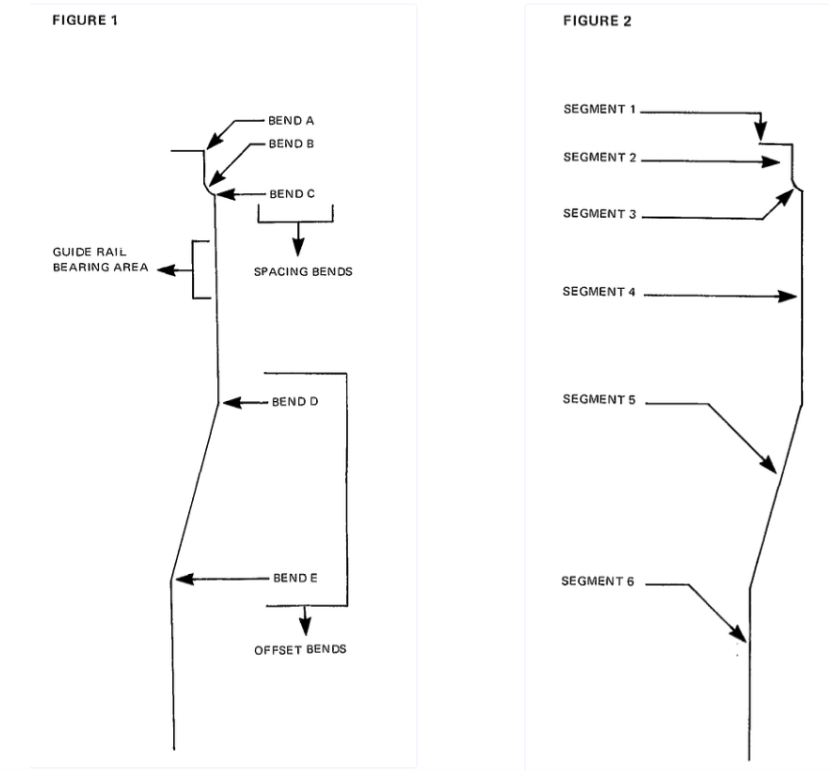

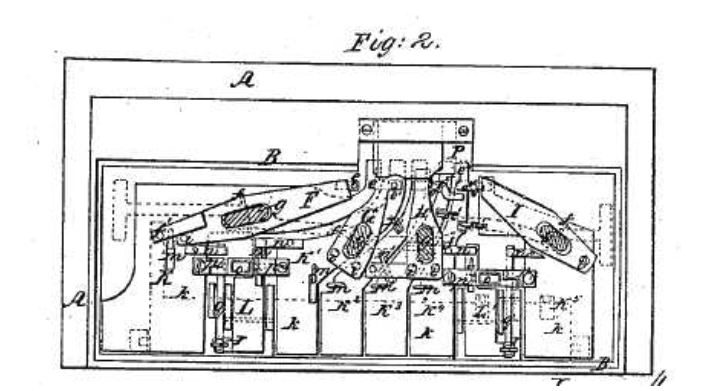

Zachariae’s complex damper lift system involved four pedals, each with four operating positions, requiring lifting or pressing with the toe.

The concept of sustaining specific notes while allowing the dampers of others to continue functioning was pursued by other inventors in different ways. Goudonnet and Lentz of France and Zachariae of Germany developed complex pedal mechanisms that raised certain small sections of dampers. Although they worked on the principle of the bass sustain pedal found in many upright pianos, they used different combinations of smaller numbers of notes. However, their complexity ultimately led to their failure. Zachariae patented his design in the United States in 1869.

Moving on to the probable reinvention of the same principle in the United States in 1874, there seems to be no indication that the American inventors were aware of the European precedents. Although the evidence is not comprehensive, there is enough of it, primarily from the diary of William Steinway, to construct a reasonably convincing narrative.

On May 9, 1874, M. Waldo Hanchett of Syracuse, New York, filed a patent application for an "Improvement in Piano-forte Attachments." He received patent #153766 for this invention on August 4, 1874. He proposed to call his invention a "sostenuto pedal" (apparently the first use of this name).

The excerpts provided below are complete regarding the subject covered since Steinway wrote in an abbreviated style without apostrophes and other punctuation and with spelling errors:

9/23/1874 - Hanchett from Syracuse has perfected his Appara-tus on a style 2 Grandpiano, it is splendid

10/02/1874 - Theodore, sends a new patent to be caviated, to be sostenuto pedal

10/08/1874 - Albert & I take Alberts new sustaining pedal patent to Van Santvoord & Hauff who think that it is perfectly patentable

10/24/1874 - to my joy a letter is received from Wm. Hauff, that Alberts Sustaining Pedal has been granted. I telegraph to Theodore “Alberts Patent granted at Washington”,William Steinway

10/27/1874 - Show young Hanchett Alberts Patent and tell him that we do not want to enter into an contract with his father

Based on this account, it appears that Hanchett decided to attempt to license his invention to Steinway (and possibly others) by sending his son to demonstrate it. Presumably, there were some issues, so Hanchett made some improvements by "perfecting the apparatus" (9/23/1874). We must now speculate on the following events, but it seems reasonable to assume that William sent word to his older brother Theodore, who was in Germany, about this promising new invention. About a week later, Theodore submitted a patent design for such a sostenuto pedal (Note that he used the same name as the one in Hanchett's patent abstract). However, this design also required some tweaking, so Albert worked on it for a few days, and they took it to their patent attorney for review.

The Steinways filed for a patent on October 15, 1874, and received patent #156388 in less than two weeks, on October 27. They seemed to have had influence in the patent office for expedited service, and it is likely that there was no thorough search of prior patents; otherwise, Hanchett's patent would have been discovered. William Steinway then visited young Hanchett to demonstrate that the Steinways had no need for his father's sostenuto system. It is uncertain whether Steinway knew that Hanchett had received a patent for his invention.

The Steinway brothers filed for a patent on October 15, 1874, and received patent #156388 in less than two weeks, on October 27. It seems they had influence in the patent office for expedited service, and it is likely that there was no thorough search of prior patents; otherwise, Hanchett's patent would have been discovered. William Steinway then visited young Hanchett to demonstrate that the Steinways had no need for his father's sostenuto system. It is uncertain whether Steinway knew that Hanchett had received a patent for his invention. The Hanchetts filed a claim and subsequent lawsuit. During their defense, the Steinway brothers found Zachariae's pedal design and learned about Montal's exhibitions:

On April 5, 1875, Albert went to Washington with Hauff to oppose the patent controversy. He brought Zachariae's pedal design with him but forgot the grand piano mechanism drawing. On April 25, 1875, Theodore brought the information from Maxwell that Montal had exhibited the Sostenuto pedal at the 1862 London exhibition.

They found a copy of the musical jury report in their safe, which they showed to Hauff and sent to Washington. The existence of the two previous designs by Zachariae and Montal proved that Hanchett was not the true inventor of the Sostenuto, calling into question the validity of his patent. Later, the Steinways found evidence of Montal's earlier exhibition in 1855 in the Paris Exhibition jury reports (this is the primary source for the idea that Montal was the inventor).

On May 10, 1875, they received a letter from Hauff that Commissioner Spier had resolved the patent dispute between Albert's patent and Hollenberg and Hanchett's application, and both the latter were rejected due to the 1855 Paris Exhibition jury reports.

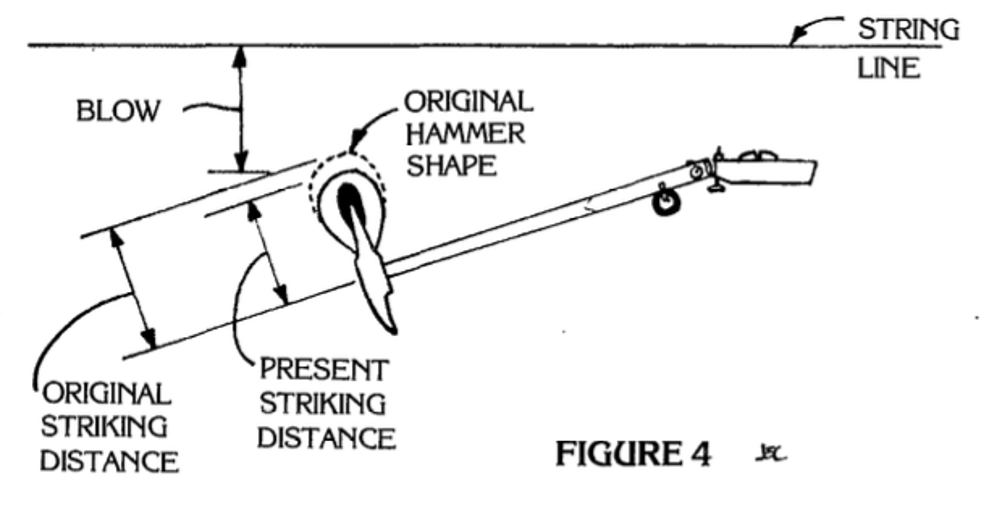

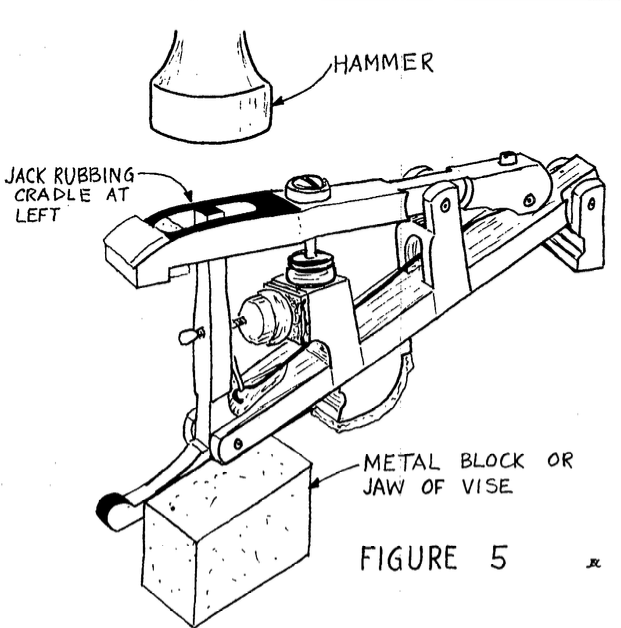

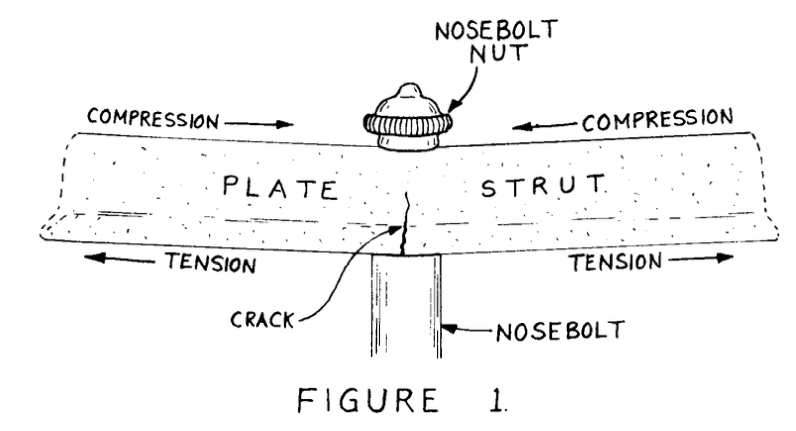

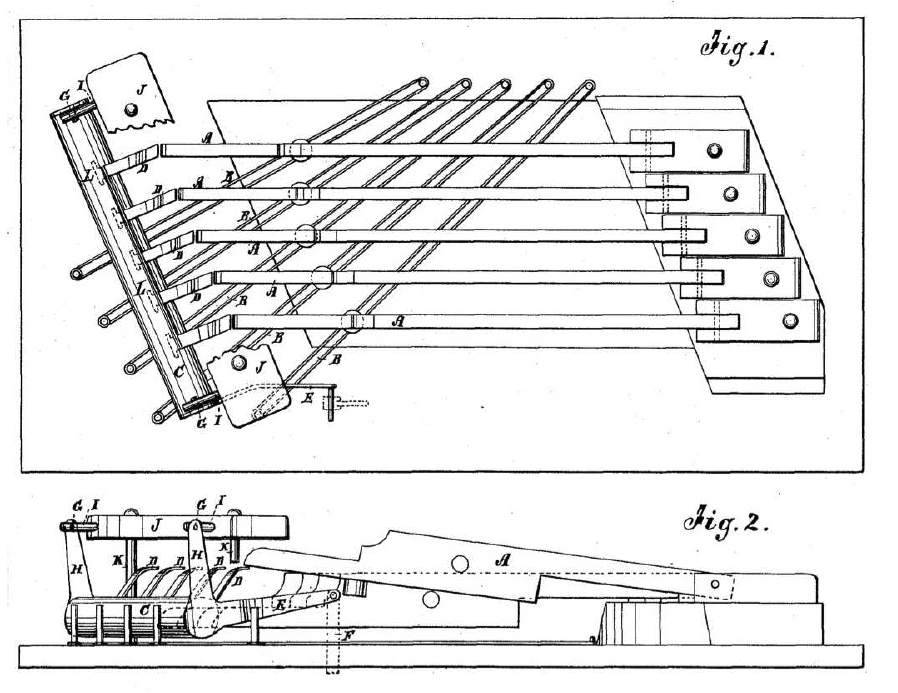

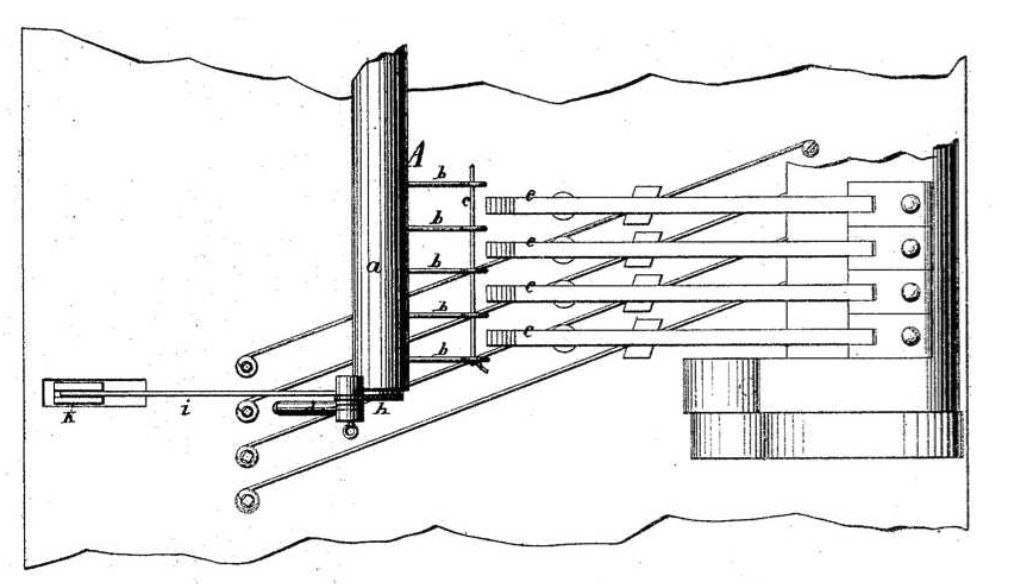

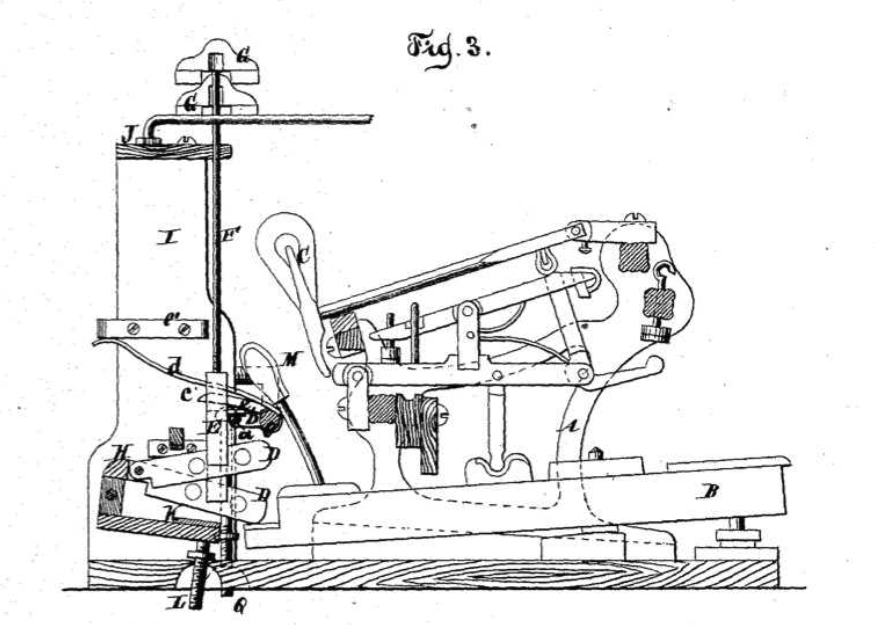

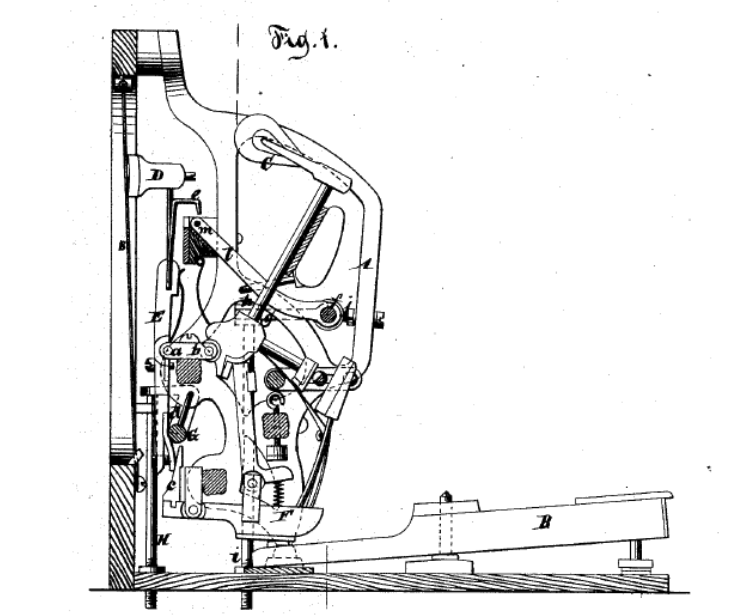

Meanwhile, Albert Steinway had committed himself to improving his design. His initial design only applied to square pianos (like Hanchett's), holding the ends of the hammer shanks above the strings instead of within the action itself. On May 15, 1875, he submitted three patents: 164052, 164053, and 164054, respectively for grand, vertical, and square pianos, which were approved on June 1. The patented designs for the grand and vertical piano actions were very similar to those used by Steinway today.

Steinway sustained design for grand piano

Steinway upright piano design

The design for the square piano was modified so that the sustaining pedal lifted the hammers through a tongue in the middle of the lever instead of lifting the end of the lever. Hanchett also submitted and obtained a patent for an improvement on his original design, filing the application on March 6, 1875, and receiving patent #168484 on October 5. Again, Steinway received much faster service from the patent office, with two weeks instead of Hanchett's seven months.

Steinway decided to include this pedal on all their grand pianos, and because their pianos were so successful on the concert stage, that option became the norm rather than a mere curiosity. Therefore, composers began to take advantage of it in their compositions, with Claude Debussy as one of the most significant pioneers. However, the number of composers and compositions that required this pedal was not excessively significant, and most piano manufacturers did not bother to include it. Broadwood, Bechstein, and Bösendorfer are some of the most important manufacturers that ignored the central pedal at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, while major manufacturers such as Yamaha made it standard only for their grand pianos at the end of the 20th century. It is clear that Steinway is responsible for the fact that most grand pianos today include a sostenuto pedal.

The story is fascinating and reveals much about the history of piano development.

What's Your Reaction?