The Bumping action

The article describes the early forms of Bumping action, one of the fundamental features of the piano. It illustrates the structure of the hammer, the mechanics of the keyboard, and its evolution over time. The various forms of Bumping action are highlighted, with particular attention to variants that allow for greater hammer movement and an increase in the kinetic energy transmitted to the piano strings. The text also provides a description of the different depths of the keyboard and the touch weight in the various types of Bumping actions presented. Additionally, it illustrates the presence or absence of dampers in sound production.

This article is based on the writings of Walter Pfeiffer. The text provides valuable and informative information on the subject matter, and it is emphasized that the article is based on the author's personal experience. It should be noted that the opinions expressed in the article are personal and do not in any way bind Walter Pfeiffer or other individuals mentioned in the texts used for the writing of this article.

The fundamental characteristic that sets all bumping actions apart is the hammer setup. In bumping actions, the hammer assembly, consisting of the hammer head, shank, and butt, is attached to the key and pivots on it. As a result, the hammer and key move together during the bumping action, with the hammer assembly commonly taking the form of a two-armed lever. Typically, the hammer is activated when the hammer tail hits an obstacle. In some instances, a secondary lever called the "escapement lever" is utilized. In early forms, the back bar or continuous fixed rail known as the "bumper rail" served as a stop. In more recent variations, individual levers referred to as "escapements" or "hoppers" replace the continuous rail, providing the let-off in a bumping action.

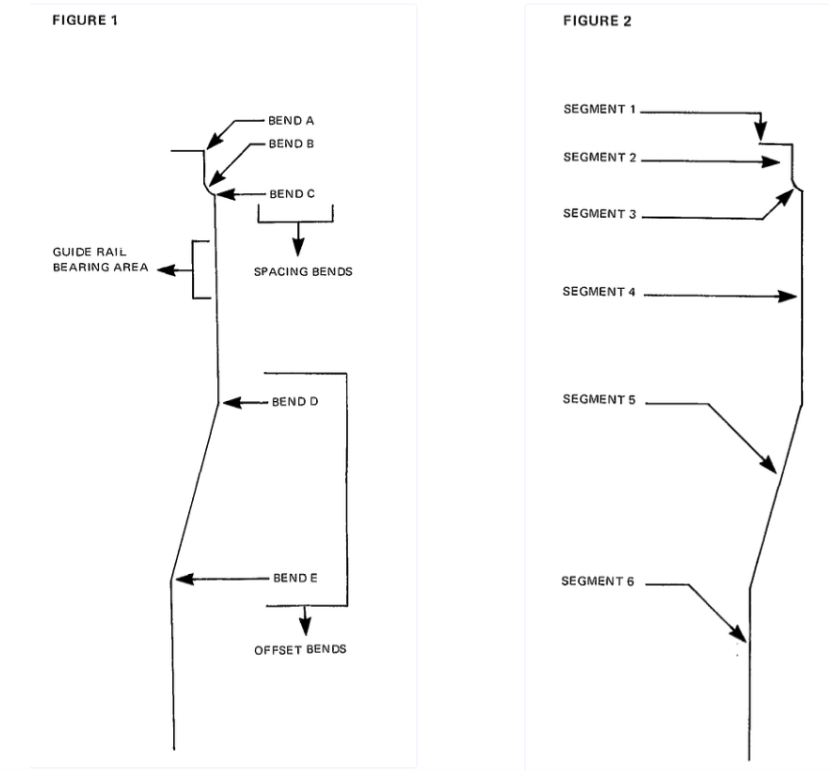

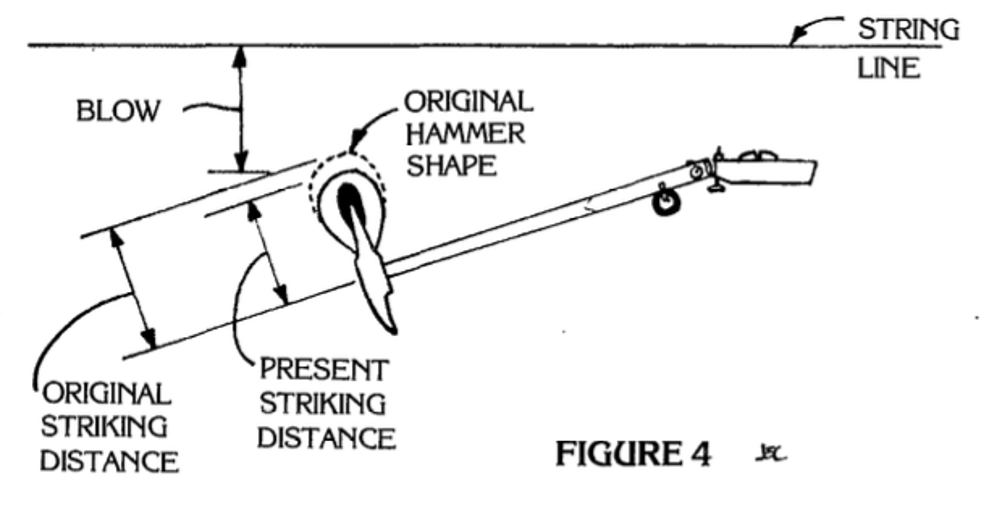

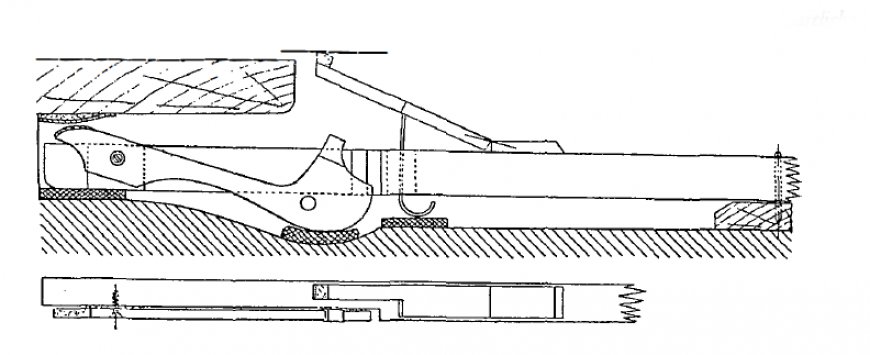

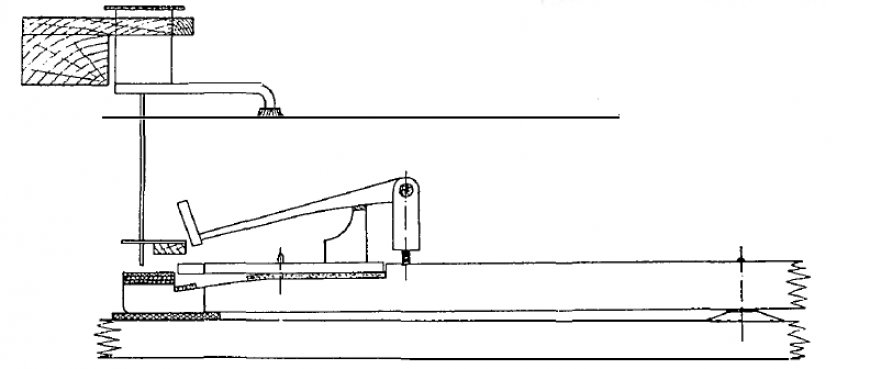

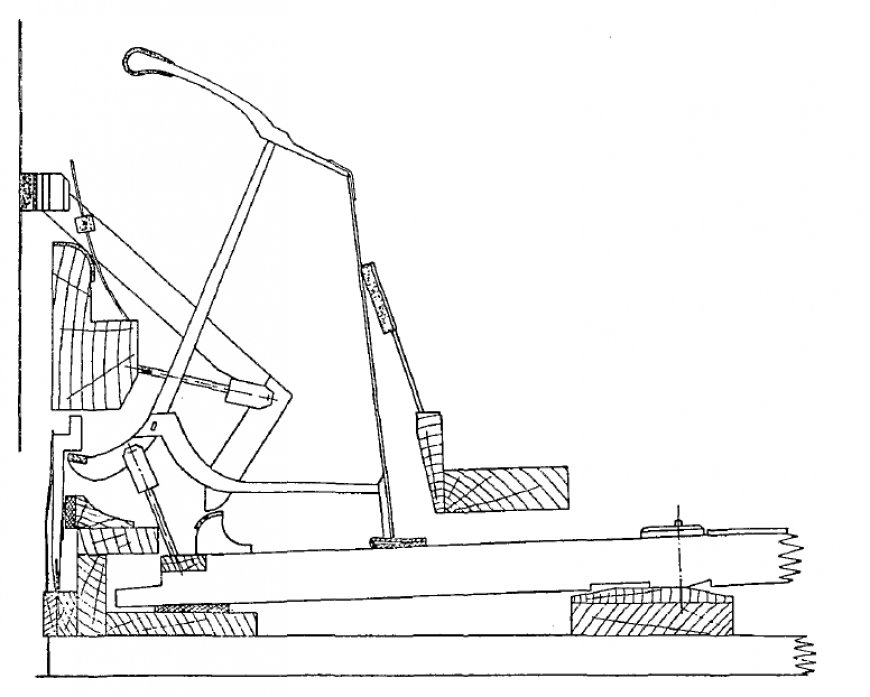

One of the earliest and most straightforward forms of the bumping action is depicted in Figure 1. As usual, the key is a two-armed lever, and at its rear end, a delicate hammer assembly, likewise a two-armed lever, lies flat. The key's end is angled, and the hammer assembly's pivot point is where the bevel begins. The hammer assembly is simply attached to the key by a leather strip that is glued to both pieces. The leather simultaneously functions as a center pin. The hammer shank is rectangular in cross-section and measures 1 by 6 millimeters in the treble. Attached to it, pointing toward the player, is the tiny hammer, which weighs just one-fifth of a gram in the extreme treble. When the key is struck, its back end rises, the hammer tail hits the cushioned back bar, and the small hammer is launched towards the string with kinetic energy equivalent to that transmitted to the key.

Figura 1

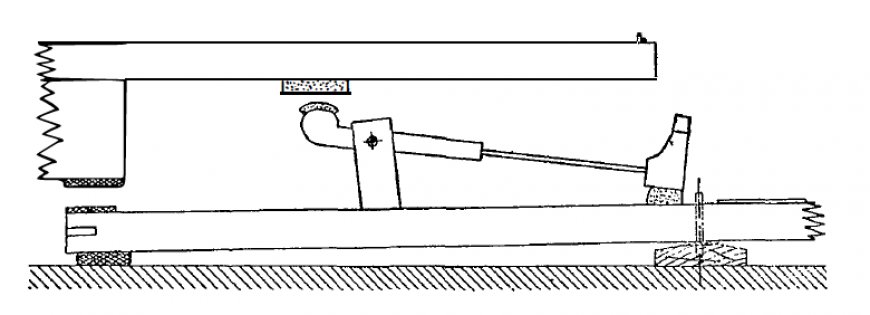

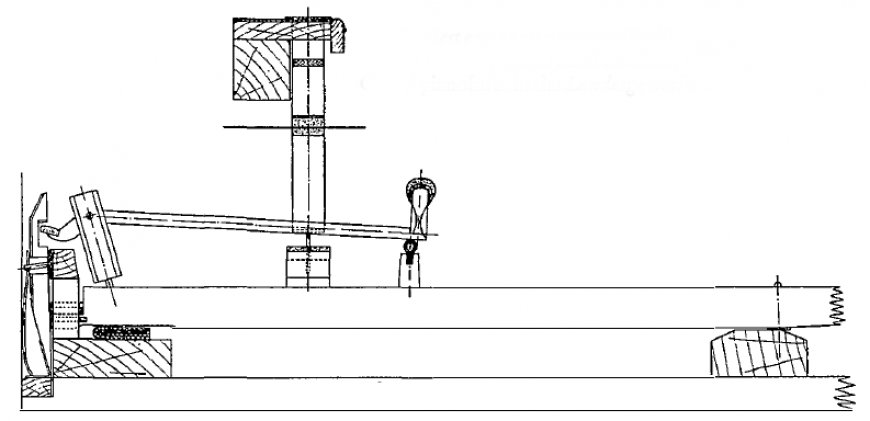

The touch weight of this action ranges from 4 to 6 grams, with an average key dip of 6 millimeters. Dampers are not present and are unnecessary for producing the delicate sound generated by this action. Another early form of the bumping action is illustrated in Figure 2. In this setup, the hammer assembly is fastened on the sides and pivots on a screw in a correspondingly hollowed-out area of the key's back half. Sachs refers to this arrangement as the "most original form" of the bumping action and claims that it preserves the archetype of the bumping action. In the small square piano depicted in our figure, the touch weight is 22 grams, and the key dip is 3 millimeters.

Figura 2

To provide the hammer assembly with greater freedom of movement, and therefore more kinetic energy, the arrangement shown in Figure 3 became increasingly popular in this and similar variations. The hammer assembly is no longer inadequately and compactly mounted on the key. Instead, it is "pivoted in a wooden fork fixed rigidly to the key, pointing upward, called the flange, in such a way that the hammer tail, which protrudes on the other side of the fork, must strike against the bumper rail." According to Marx, the touch weight of the small instrument he examined was 12 grams, and the key dip was 4 millimeters.

Figura 3

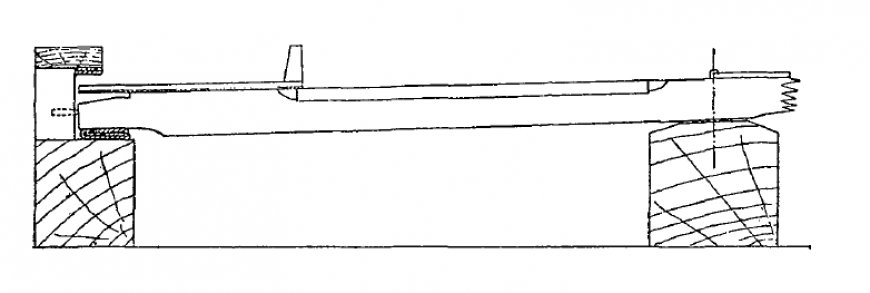

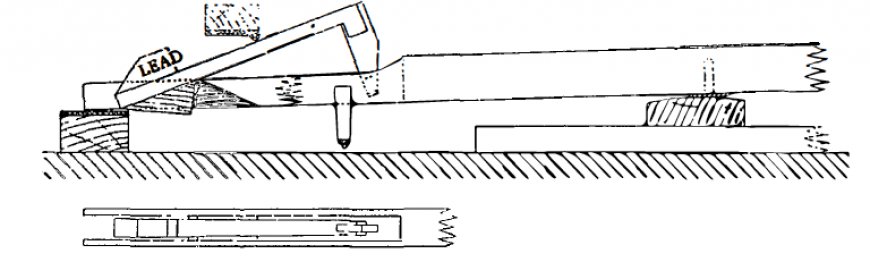

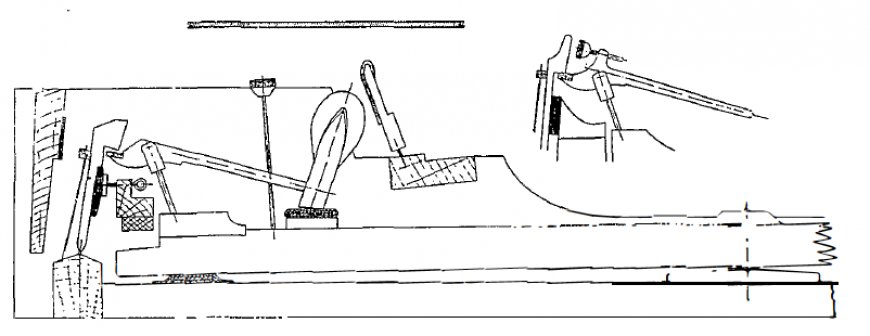

So far, the mechanisms discussed have involved horizontal and upward striking, but the bumping action can also be found in a downward-striking form, as shown in Figure 4. The key's back half is slotted. The small hammer assembly is seated in the slot on the key's back half, held in place and pivoted on a piece of parchment. The bumping and striking of the string both occur on the same arm of the lever, with a back lever arm to accommodate a lead weight. The lead weight's function is to return the hammer to its resting position, allowing it to be launched once again towards the string. We constructed an action model of this mechanism, and on our model, the key dip is 5 millimeters, and the touch weight is 22 grams. Further information can be obtained from the drawing.

Figura 4

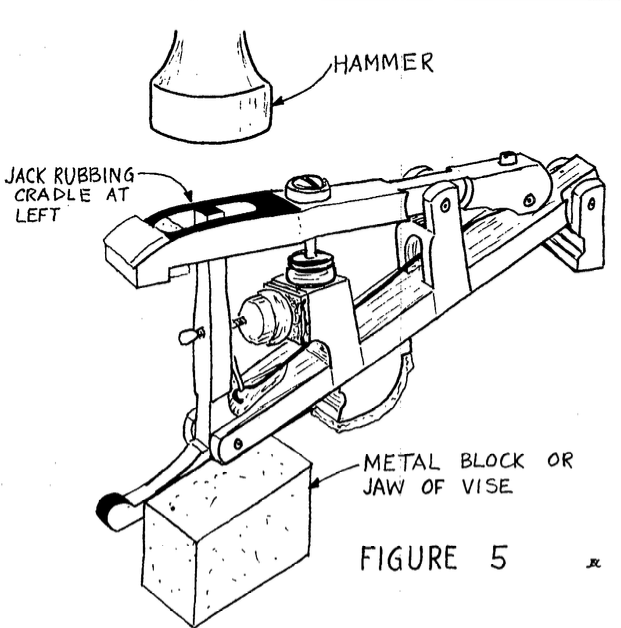

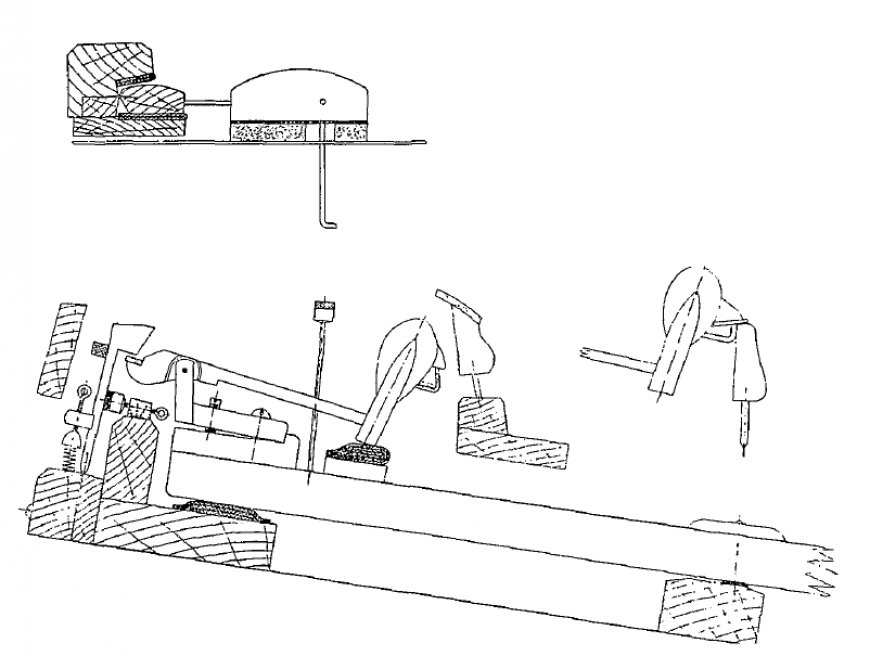

Figures 5 and 6 show unique forms of the early bumping action, featuring a two-armed escapement lever interposed between the back bar and the hammer. In the first example, the hammer assembly and the key's back half act in opposition to each other, whereas in the second, they act in the same direction. Sachs refers to the former as a bumping action, as do we, but he refers to the latter as a pushing action, evidently influenced by the direction in which the hammer assembly faces. We cannot agree with him on this. It could possibly be classified as a hybrid form, but the overall construction is undoubtedly that of a bumping action, deviating from traditional forms only in that a two-armed lever is inserted between the bumper rail and the hammer assembly, and the latter acts in the same direction as the key's back half. However, the determining factor in classifying this as a bumping action is neither the secondary lever nor the direction in which the hammer assembly faces, which, for us, is beside the point. The essential feature of all bumping actions is simply the attachment of the hammer to the key.

Our fifth figure depicts the same action found in H.C. Hayne's 1977 small square piano in the Berlin Collection (No. 337). Curt Sachs refers to it as a "bumping action with an escapement lever," but provides no illustration. Rosamund Harding's book contains the illustration Sachs mentioned.

Figura 5

Figure 6 depicts the action of I.J. Senft's small square piano in the Berlin Collection (No. 1280, hammer action illustration 9). Sachs labels it a "pushing action with hammers turned backward, attached to the keys with metal flanges and with escapement levers with jacks seated firmly upon them which activate the hammers." Heyer's Catalogue also lists a small square piano with the same hammer action as shown in Figure 6 under No. 113. Georg Kinsky agrees with our classification of this as a "bumping action." Otto Marx, the restorer and caretaker of this collection, notes that the touch is light and flowing in both actions, with a key dip of 5 millimeters and a touch weight of 18-25 grams for Figure 5 and a key dip of 7 millimeters and a touch weight of 15 grams for the action in Figure 6. In the small square piano depicted in our Figure 6, the key dip is 6 millimeters, and the touch weight is 10 grams. The touch is light, and the repetition is excellent.

Figura 6

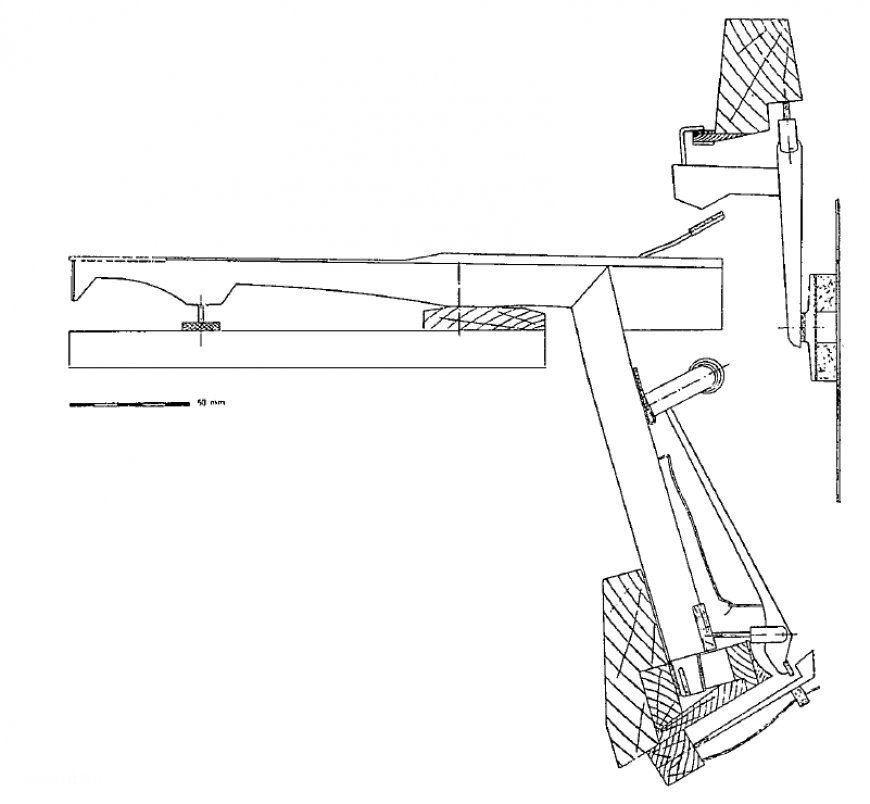

Johann Andreas Stein (1728-1792) made the most significant and critical improvement to the bumping action by replacing the fixed bumper rail that ran the width of the instrument with individual escapements (or hoppers). This excellent innovation gave the player control over the strike. Initially lacking back checks, Stein's action underwent further modifications, mainly of a technical nature. Nonetheless, the fundamental arrangement of the "German action," which is often referred to as Stein's work, can rightly be credited to him. Stein gave the bumping action its final form, which it has retained to this day, over a century and a half later. The world-renowned "Viennese action" is none other than Stein's escapement (or hopper) action, taken over and enhanced in a few technical aspects by Stein's daughter Nanette and her husband, the piano artist Johann Andreas Streicher.

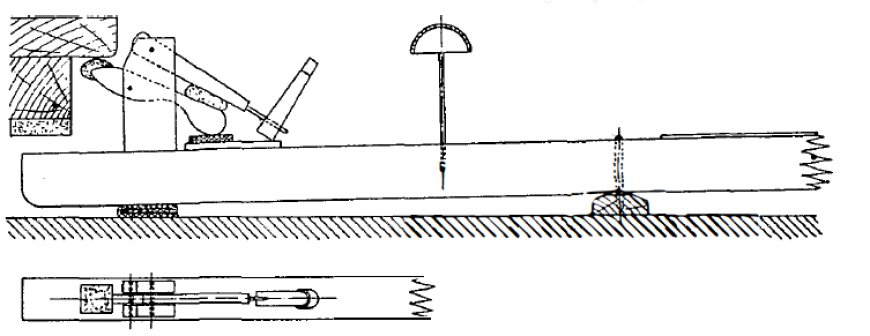

We invite the reader to refer to Figures 7 through 10. The touch of the Stein grand piano in the Provincial Museum of Trades and Crafts in Stuttgart is exceptionally light. The letoff resistance is barely noticeable, and the repetition is superb. The key dip is approximately 6 millimeters, and the touch weight is 30 grams in the bass and an additional 20 grams in the treble.

In his Geschichte des Claviers (Leipzig, 1868, p. 206), Oskar Paul mentions an action manufactured by Besendorfer in Vienna, which he describes as "a most happy combination of the German action and the English jack action." The accompanying illustration shows that the action in question is a bumping action, differing from conventional ones only in that the escapement hangs rather than standing upright.

Figura 7

Currently, the Viennese action is widely known, and its design and mode of operation require no further explanation. Other books contain any information anyone could wish to know about this action. A much more important question in our minds is why this originally outstandingly good mechanism could have been displaced by the jack action.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel, whom we have already mentioned, spoke highly of the Viennese action, stating that it could be easily manipulated by the most delicate hands and allowed the player to lend inspiration to their performance. This was because it had a distinct, reliable response and did not impede fluency by requiring too much exertion. Moreover, it was durable and only half as expensive as the English action. The latter did not permit the same degree of dexterity in playing as the Viennese action because the much greater key dip cramped the player's style to a certain extent, and the hammer letoff was slower when a note was struck repeatedly. In short, this action, which undoubtedly had its advantages, was not as well suited to such variegated tonal shadings as the Viennese action. In contrast, the English action choral instruments added a distinct charm and euphony to choral music. However, their effect was only noticeable in smaller rooms and not in larger ones, where they were not as forceful as grands with a Viennese action. This was the situation in 1828, but only 15 years later, Karl Klitzing wrote in the preliminary remarks of one of his works that he would not mention the Viennese action because it was outdated. He believed it would make more sense to not describe it in a work on fortepiano building.

Figura 8

On the other hand, in 1864, Welcker was still largely in favor of the Viennese hammer action: "Of all the actions invented up to now, the German action is the simplest and most durable. Many piano virtuosos prefer the jack action to the German, but they cannot explain why. Prominent pianists, whom I asked for their honest opinion, explained that this preference was due to what the player was accustomed to."

This preference was not present in Germany, where the jack action was prevalent. However, in Austria, the homeland of the Viennese hammer action, there were still those who cherished it, even though it was no longer in a secure position. These individuals clung all the more ardently to their traditional bumping action. For instance, in 1931, August Kogler in Graz wrote in the Zeitschrift fur lnstrumentenbau that even today, many were still sold on the grand with the Viennese action, particularly among piano teachers and professional musicians. In 1942, Wolfgang Hutterstrasser of the firm Besendorfer in Vienna reported a similar situation in a letter to the author.

Figura 9

What could have caused Klitzing to reject the Viennese action? There is no direct information on the subject in his works, so we must rely on conjecture. However, if his reasons were valid, even we of today should be able to rediscover them. It could not have been a matter of repetition, which tends to be of primary importance to us today, because otherwise, Klitzing would have been more amiable towards a repetition action such as that of Erard. In his book,Theoretical and Practical Handbook of the Art of Fortepiano Building, there are comments that help us understand this matter. In regards to letoff, he writes that the decisive features of a good hammer action are that it is quiet in operation and that the hammer lift and letoff are not too noticeable. It is also crucial that the player does not feel the falling back of the hammer, as it produces an annoying sensation.

When we compare the Viennese action to today's jack action, we can clearly see that the Viennese action, especially in its heavier forms, feels somewhat bumpy and has a certain noisy sluggishness and stiffness, especially to someone with an exacting touch. These characteristics are precisely what Klitzing considers the hallmark of a good hammer action, which the Viennese action lacks.

In the Viennese action, several things occur simultaneously: the hammer tail bumps against the lip of the escapement, particularly in the case of rapid, repeated blows, where the hammer is prevented from falling back very far. Additionally, the hammer strikes the string, then catches on the back check. Finally, the hammer falls back, which has either not been caught by the back check or has been released by it.

Therefore, when the hammer is attached to the key, everything that suddenly affects or to a certain extent disturbs its movement can be felt by the player via the key as roughness. The heavier the hammer, the shorter the front lever arm of the key, the greater the key dip, and the older the felts and/or cloths, the more pronounced this effect becomes. Due to the hammer being attached to the key, the player is more or less compelled to experience in some way everything that happens to its movement. This is not to say that the jack action is free from perceptible resistances, but its touch is so much softer and more yielding than that of a Viennese action that there is simply no comparison.

Simon Sabathil has developed a hammer helper spring, bent at an angle, to lighten the touch of the Viennese action. It is inserted between the key and the hammer shank, and it is screwed tightly to the key to reduce the weight of the hammer so that it barely falls. Sabathil wrote to the author that the weight of the hammer is almost lifted by the spring. Following his specifications, they made such a spring, installed it in their action model, and obtained a touch that was lighter by half and substantially more yielding.

However, this experiment raises a question: whether the advantage of such a drastic counterbalancing of the weight of the hammer is not achieved at the expense of a considerable loss in dynamic possibilities. For further details, see Sabathil's article "Eine Verbesserung der Flugelmechanik Wiener Systems" ["An Improvement on the Viennese-Type Grand Action"] in the Zeitschrift fur lnstrumentenbau, Vol. 55, 1934/35, p. 293.

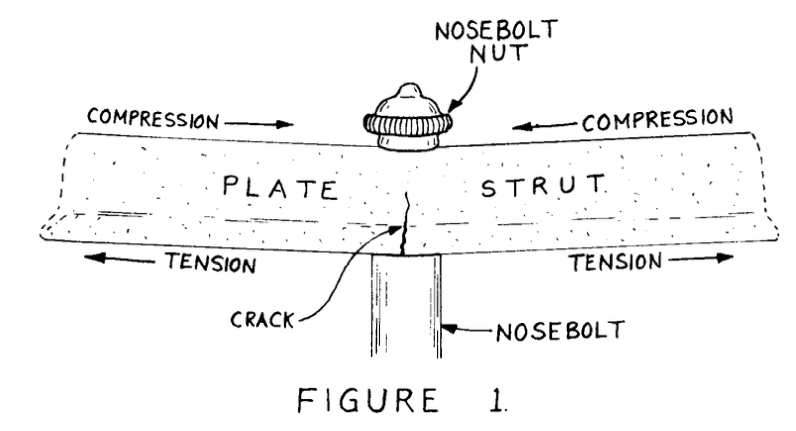

Another shortcoming of the hammer attached to the key is that the hammer pivot point is not fixed in position. As a result, the blow varies according to the pressure applied at the key and is not precise or clearly defined, especially in the treble. Welcker called attention to this fact in 1856, noting that the striking point can shift forward or backward, depending on the movement of the key.

Steinhausen held this imprecision of the hammer blow to be directly responsible for the fall of the Viennese action. He stated that the key/hammer action is set up in such a manner that the hammer must always strike the string at exactly the same spot. The English action's victory over the older German action was due to its greater precision in regard to the striking point.

Figura 10

Apart from technical considerations, the main objection to the Viennese action in modern times is that it has "no repetition" (Kohn 16). However, from our point of view, this criticism largely overlooks the facts. In terms of repetition without the hammer needing to fall all the way back, few other actions surpass the Viennese action. It is only when the hammer has fallen back a significant distance that the hammer tail cannot catch on the escapement lip until the key returns to its rest position.

Regarding the repetition of the Viennese action, Wolfgang Hutterstrasser (from Bosendorfer), together with his factory manager Karl Georg Berger, wrote: "If the key dip is 8.4 millimeters and it is allowed to return 4.9 millimeters, which is more than half its stroke, a new blow can be struck with the hammer. However, if one waits slightly longer, the key must go all the way up before the hammer is ready for another blow because the hammer slides off the back check and back onto the hammer rest felt. Hence a rapid repetition is possible only when the key is released just enough that the hammer has no time to free itself from the back check and fall back onto the key. However, this can only be achieved with a great deal of skill and experience, and chance hits will always be a factor." (From a letter)

The repetition of the Viennese action is somewhat similar to that of our present-day upright action, and we believe that even with an average Viennese action - provided it is well designed, correctly installed, and regulated - the repetition must be more than satisfactory for a player who is thoroughly familiar with their instrument.

In our short book, "Grand or Upright?" we discussed repetition, and what we had to say in favor of the upright action can also be applied to the Viennese form of the bumping action. However, despite our defense, the fact remains that, like the conventional present-day upright action, the Viennese action exhibits a gap that requires playing skill and proficiency to overcome. In isolated cases, it can be bridged only with difficulty without a supplementary repetition device. With the concert hall in mind, this not completely guaranteed repetition must be viewed as a shortcoming. In fact, it is one of the reasons why, for example, Bosendorfer in Vienna began to limit the production of its "Viennese grands" as early as the beginning of the 20th century, and discontinued them altogether in 1909 (although during the war from 1914 to 1918, a few instruments were made to use up the remaining stock).

However, the so-called Viennese action is still being used to this day - at least in Vienna - by manufacturers of less expensive grands. So even now (in 1947), it remains in use.

Figura 11

To summarize, it can be said that the living conditions for the bumping action have deteriorated compared to the pushing action. This is because the evolution of the piano was primarily driven by the desire for a greater volume of sound, which required increased key dip, heavier hammers, and sturdier parts. These changes highlighted defects in the hammer attached to the key, which were barely noticeable during Stein's time. Even the repetition, which was originally sufficient for all requirements, became less satisfactory.

Despite this, outside of the concert hall, custom and taste may still cause someone to choose the Viennese action over the jack action. However, the arguments against the Viennese action are not compelling enough to prevent its ultimate demise.

Even August Kogler's labor of love, which successfully designed a repetition device for the Viennese action, will not change anything. After gluing both layers of felt to the hammer molding, Kogler attaches a "nose" to the hammer top felt on the side facing the back check, which is covered with leather. He supports this from below with a "brake shoe," set back slightly. According to the German patent, as the hammer falls back, the back check, which is fixed in position and not covered with felt or leather, should catch and hold it on the nose-shaped piece. If one releases the key moderately, the hammer remains in its raised position, supported by the nose and back check. The escapement can quickly and reliably reengage the hammer tail, and the action is ready for a new blow. Only when the key is released almost all the way can the hammer return to its true rest position.

On the action model provided by the inventor himself, the arrangement differs slightly from that shown in the patent. The back check is provided with a slightly curved, projecting leather top piece 3 to 4 millimeters thick, which can hold the hammer up as it falls back, although not as firmly as a conventional back check. In our model, the nose brushes lightly against the top piece as the hammer travels upward, but as the hammer falls back, the nose catches on the top piece because the hammer pivot point has shifted and brought the hammer head closer to the back check and its top piece. A proper, tight checking of the hammer, as we know it and as it occurs in the conventional Viennese action, is lacking here.

After repeated tests on the action model, we do not doubt that Kogler has managed to improve the repetition of the Viennese action in such a way that it can truly meet any demand made on it. However, it must be said that this repetition action, while serving its purpose and supposedly durable, still has features that make it decidedly inadequate and incomplete. The top piece on the back check can never be as good as a repetition lever with a spring, and the entire arrangement still does not eliminate the other defects of the hammer attached to the key. In fact, in our opinion, it increases the bumpy feel of the Viennese action.

What's Your Reaction?