The Érard Piano at the 1844 Exhibition

This article discusses the preeminence of the Érard piano, considered by many as the perfect instrument, and its impact on the piano industry. The article highlights the history of the Érard family and the genius of Sébastien Érard, whose innovations contributed to the instrument's perfection. The article describes the European reputation of the Érard piano, which replaced the pianos of England and Germany, and how it was accepted for concerts in salons and public halls in England. The article also talks about the competition in the piano industry and how other makers sought to imitate the improvements of Érard to remain competitive. Finally, the article narrates a story of a visit to a piano maker in Cologne, where the Érard piano was imitated and admired.

Over the last fifty years, as the field of industrial arts has flourished, there has been no mechanical production, particularly musical instruments, that have reached such an outstanding level of perfection as the pianoforte. This outstanding achievement is undoubtedly due to the unwavering dedication of the Érard family to the advancement of their craft over sixty years, particularly the genius of one member, Sébastien Érard.

Frequently, it is said that the Érard piano is so impeccable that further improvement seems impossible, yet it continually evolves. Undoubtedly, it will continue to advance with the assistance of its enlightened leaders, who will dedicate their experience, studies, and resources to maintain the superiority of the Érard family over competitors, not only in Paris but throughout Europe. In fact, the reputation of Érard extends throughout Europe, and it is rightfully considered the pride of French manufacturing.

Before its establishment in 1780, we relied on pianos from England and Germany. Nowadays, however, Érard pianos are nearly the only ones accepted for concerts in salons and public halls of England. In Italy and Belgium, Érard pianos have replaced the less expensive pianos of Vienna, as Érard sells twice as many. In Germany, where pianos are manufactured in significant cities along the Rhine, the most reputable makers among great artists and amateurs are those who attempt to replicate the improvements of Érard. Last autumn, during a trip down the Rhine, our French pride was particularly flattered by an incident worth mentioning. After passing through Belgium, where all first-rate artists appreciate Érard pianos, we were eager to examine the current state of piano manufacturing among our predecessors in Germany. Upon arriving in Cologne, the capital of Rhenish Prussia, we visited the piano maker with the best reputation in the city. In his shop, we were surprised to find only two grand pianos, one of which was adorned with the German maker's embellishments, while the other was an Érard from Paris. Upon scrutinizing both instruments, we quickly realized that the first was a copy of the second, and we informed the foreign maker of how honored we were to see the invention of one of our countrymen so well appreciated on the banks of the Rhine.

In Petersburg, Érard pianos, which Thalberg was the first to popularize, are so fashionable that they are imported from London and Paris despite the transport costs and thirty percent import tariffs. What do the makers in this capital do to compete against such superior competition? They attempt to imitate Érard pianos in any way possible and abandon the principles of Vienna and London, which they had previously followed. In Russia, as in the rest of Europe, English and German-type pianos are no longer valued since the superiority of Érard pianos, with their new principle, has been recognized. It is unsurprising, therefore, that makers in Vienna and even London must alter their practices.

In earlier eras, English pianos were boasted of among us. Our Anglomania in this respect can be explained always from the same source, that is to say, the interests of the speculators who have imported and sold English pianos in Paris. From 1785, the importation of English pianos was already so considerable that the merchants of these foreign pianos tried to place barriers against the early manufacture of Sébastien Érard in Paris, which from the beginning menaced their commerce with total ruin.

Later, in the Restoration period, there was an attempt to revive the sale of English pianos in Paris. There was much talk of instruments arriving from London, but the protective policies of the government of the empire, being designed to prohibit foreign pianos, opposed this extension of commerce. Some then thought of claiming that some English pianos were made in Paris. At the same time, in a rather remarkable contrast, the Érards took out a patent in London for their new piano, and went on to acquire for that instrument the reputation they had enjoyed for their harp since 1792. We believe we must insist here on a remarkable fact, that the pianos designated in France under the name of English style were nothing else but pianos with simple escapement, which the Érards had been producing in Paris for twenty years already. The first grand pianos made in France were established on this principle by the Érards between 1795 and 1800.

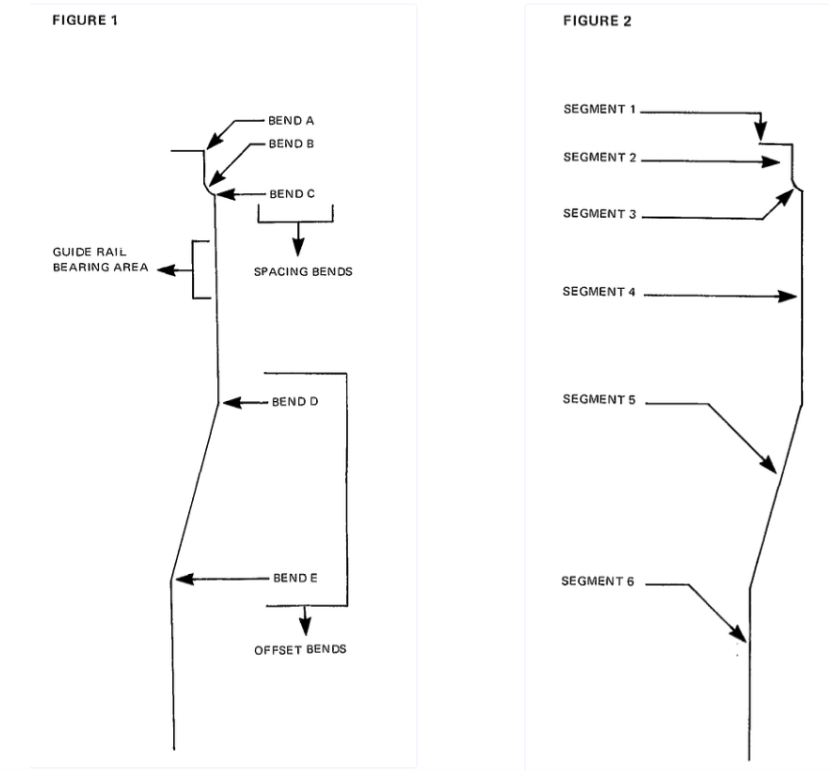

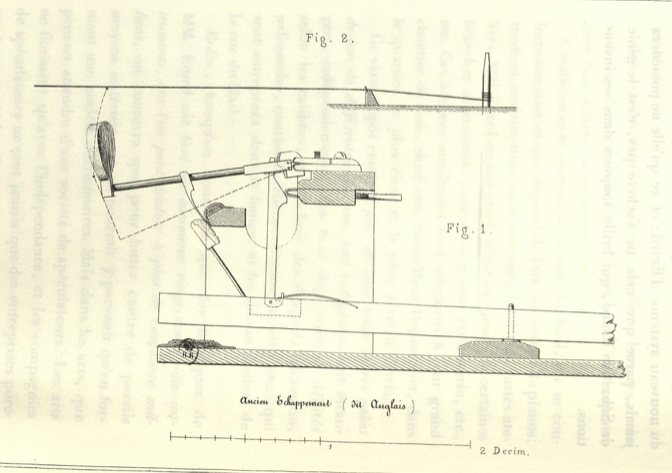

Figure 1 of Plate 1 depicts the action mechanism that most Parisian makers still follow, with some alterations in certain cases concerning the parts' positioning. Nonetheless, the principle remains the same, and the action is unsatisfactory in numerous crucial aspects, particularly in the lack of keyboard nuances. Even the great masters of the time, such as Steibelt and Dussek, complained of these shortcomings, although their piano treatment did not necessitate the quickness and force required by contemporary styles.

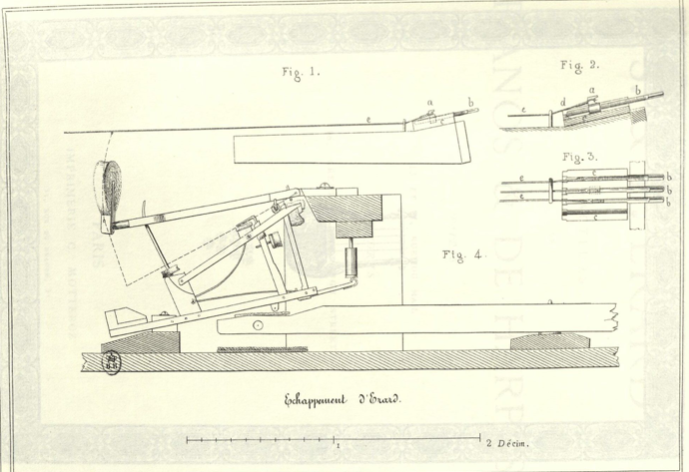

Influenced by these critiques and driven by their desire to approach perfection in their art, the Érards, unconcerned with profits, abandoned the simple escapement and embarked on new research. Their ambition was to create and manufacture a system that left nothing to be desired and fully satisfied the great pianists. After ten years of research, labor, and sacrifices, their new piano system appeared around 1810, marking the prelude to the current Érard system. Despite the criticism, the new invention made a significant impact on the musical and academic world of the time. The Institute acknowledged the invention with a report, and many professors and distinguished amateurs remember the effect the great masters of the time produced when playing on this instrument, particularly Dussek in his public concerts at the Odéon.

The invention of the new Érard escapement system is a testament to the Érards' genius and perseverance. Since its first appearance in Paris and London around 1820, its superiority over the old system was undeniable. Time and experience have demonstrated that of all the piano actions, Érard's holds up the best and is the easiest to regulate with precision. It is the only action that can suitably interpret the inspirations of the great masters and all their nuances. Moreover, we see nearly everyone abandoning pianos of the old system for those of Érard.

Despite the opposition from the English makers, who were advocates of the old system and wished to sustain it for their fortunes, the triumph of the new action was inevitable. Public opinion in France and England has irrevocably judged the issue, and the privy council of the king solemnly judged it in London.

The Érard patent for the new piano system was set to expire in 1835, but the difficulties of establishing a completely new and challenging work, coupled with the opposition from English makers, had so hindered the operation of this new enterprise that the Érard house had invested nearly 300,000 francs without any benefit. In these critical circumstances, an appeal was made to the privy council of the king for an extension of the ordinary patent duration, which is only for fourteen years. A most severe inquest took place within the council, in the presence of lords Brougham, Lyndhurst, etc. etc., and it was proven, by the witness of competent judges and by irrefutable proofs, that the invention was superior to the old system.

Taking into consideration the service that the Érards had provided to this area of industry, creating a new branch of manufacture, the council received their request favorably, and the term of their patent was extended by seven years. This decision of the privy council of the king mad a sensation in England. It is another proof of the solicitude of the English government to protect all enterprises with the aim of improving and extending manufacture and commerce in that country. The new invention of Érard for the piano was thus received in England as was, twenty years earlier, his invention of the double movement harp. Among pianos of different types and forms, the grand piano is the instrument of choice for artists and distinguished amateurs. Other pianos, laid out horizontally or vertically, were only substitutes with which to make do for lack of space or because of their lower price. All the efforts of the Érards in establishing a new system of construction needed to be directed at first toward the improvement of the grand piano.

We have only spoken thus far of the action. It is clearly the most important part, and is ordinarily the first reef against which makers founder, for everybody can become a workman simply by working, but it is only given to a few to have a genius for the action. It is through the aid of the action that the pianist brings sounds from his instrument. One could say that the action is the bow of the piano. Consequently, the action that is prepared to make the most varied nuances of tone from the instrument is incontestably the most perfect. But the manufacture of the piano includes many other important points, such as the construction of the sounding body, the proportions of the strings, the attachment of the strings to the instrument so that they vibrate in a pure manner, etc., etc. Here is the place to recall that independently of the action, all the other important points in the construction of the piano have been perfected by the Érards.

This is well known and incontestable, the dates of the patents bear witness. It was entirely natural that the Érards, devoted to their art, were always the first to make improvements, for the simple reason that they were the first to make pianos. Starting from the beginning by order of date, we find that the Érard brothers took out a patent in October, 1809 for the construction of a new piano in the form of a harpsichord, or with a tail.5 This is the first trial of the new system that would replace the simple escapement (called the English action). This patent, in addition to the new system of escapement action, presents a new way to attach the strings on the pin block of the piano. Until that time, the strings were fixed at the pin block as they are on the bridge, that is to say, the strings made a certain angle horizontally against a pin inserted vertically in the nut (see plate 1, figure 2). In Érard’s patent of 1809, the string passes through an agraffe, making a vertical angle to the plane of the sounding portion of the string, so that the string is supported above the blow of the hammer (see plate 2, figure 1).

The improved method of attaching strings to the pin blocks of grand pianos, known as the agraffe system, was invented and established by the Érards 35 years ago. This innovation, credited to Sébastien Érard, provided a firm and secure seating for the high notes where the hammer strikes the string close to its point of support. To tune the strings with precision, Sébastien also experimented with different tuning pin models, and the most ingenious of them was represented in figures 1, 2, and 3 of Plate III.

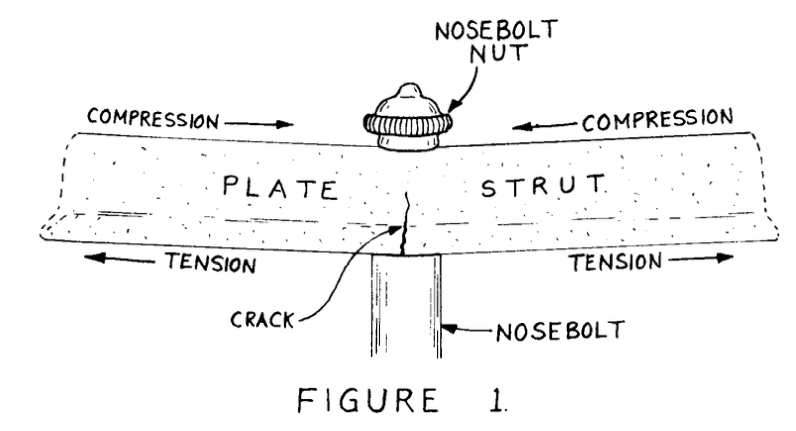

Pianos of the early 19th century were strung with fine wire, but the Érards gradually increased the string diameter to achieve a more intense quality of tone. However, the larger gauge of strings necessitated changes in the case construction to resist the pull of the strings. The Érards introduced metallic barring in 1822, which resolved the defect of cases giving way due to the resistance being found at a certain distance from the tension point. With metallic barring, pianos could be strung with wire twice the diameter, supporting a continuous tension of about 12,000 kilograms without flexion of the case.

The first piano with metal barring, exhibited by the Érards in 1823, had seven complete octaves up to C and served as a model for English manufacture. Liszt debuted on this piano, which was sent to London in 1824, before the public and the court in Windsor. Parisian makers later brought pianos from London, barred in metal on the same principle, to copy them. However, the first piano entirely barred with iron was sent from Paris to London, which remains a source of pride for the Érards.

In summary, the Érards' inventions and innovations, such as the agraffe system and metallic barring, significantly improved piano construction and quality of tone. Their dedication and perseverance in pursuing perfection in their art have left an indelible mark on piano manufacturing history.

Shortening the bass strings of grand pianos has been proposed as a means of reducing their size. However, credit for this idea belongs solely to the Érards, whose 1810 pianos were one foot shorter and had a more elegant design than their original grand pianos. Additionally, the keyboards were narrower, yet still spanned six and a half octaves. These details were noted in the Institute Reports of 1810. The Érards also made a significant improvement to the bass strings of the grand piano. They used a metal in the bass strings that was not affected by changes in temperature to the same extent as midrange and high treble strings. Around 1827, they established new proportions for the bass strings of their grand piano in London and stopped using copper-wrapped strings, which had the disadvantage of changing in pitch noticeably with temperature variations. Previously, it was common for tuners to raise the bass strings by a quarter tone during concert intermissions due to heat causing them to become flat. However, Érard pianos strung according to their new principle did not vary significantly and remained in tune. Copper strings frequently broke, which disrupted the tuning of the instrument.

The 1810 piano presented another improvement in case layout: it was the first to open with a hinge in a simple and convenient way, without the need to raise an unsightly board like in old English model grand pianos.

The harmonic bar is another recent improvement. Before its introduction, the high treble of grand pianos was never balanced with the midrange and bass, leading to a lack of intensity and purity in this area. This deficiency was completely eliminated in Érard pianos through the application of patents from 1838 and 1843.

To summarize the significant points in grand piano construction, we have:

- The new escapement of Érard from 1809 to 1844.

- The agraffe system from 1809 to 1844.

- Metal barring from 1822 to 1844.

- The use of a new principle for stringing and proportioning bass strings since 1834, which can withstand temperature changes of 15 to 20 degrees Celsius in salons and concert halls.

- The application of the harmonic bar since 1837.

All these factors, when combined in a single instrument and executed with skill, create a unique combination. One can say that the latest model of an Érard grand piano, which combines all of these advantages, is an artistic and mechanical product that approaches perfection in its entirety and in its details. In comparison, pianos of the old principle, no matter how well-made, cannot compete.

After the grand piano, the square piano is the type that deserves the most attention from the maker since it is more commonly found in salons and practice rooms compared to upright pianos. However, the square piano is the type that requires the most improvement. At the last exposition, the jury noted that these pianos did not offer as satisfactory results as the others, despite being the most numerous. Out of over 53 square pianos, the three-string piano of Érard won the prize, along with two Érard grand pianos, out of a total of only 26. Érard also obtained first place for the upright pianos with oblique strings, but only 27 were entered.

It should be observed that the square piano is the most difficult to construct well. It presents the greatest number of difficulties in its design, placement of parts for the escapement and dampers, overcoming string tension, and limited extension of the soundboard. As a result, it is the most difficult to make sound good. However, Érard presents a superior piano of this type today, possessing all the precision and nuances of grand pianos, proven solidity, and production quality previously found only in grand pianos. The Érards take pride in having resolved a very difficult problem and rendered a new service to art.

It took persistent work and repeated experiments for Érard to achieve a satisfying degree of perfection for this new piano. An escapement system different from that of the grand piano was tried to produce the same effect. The invention of the action was ingenious, but presented problems in practice, and the application of the grand system became more desirable. It became the subject of a patent in 1843.

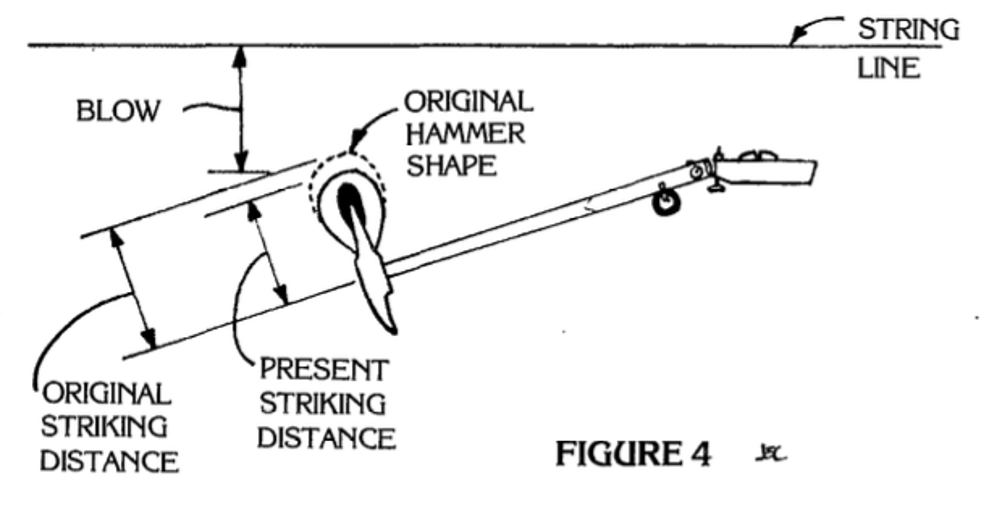

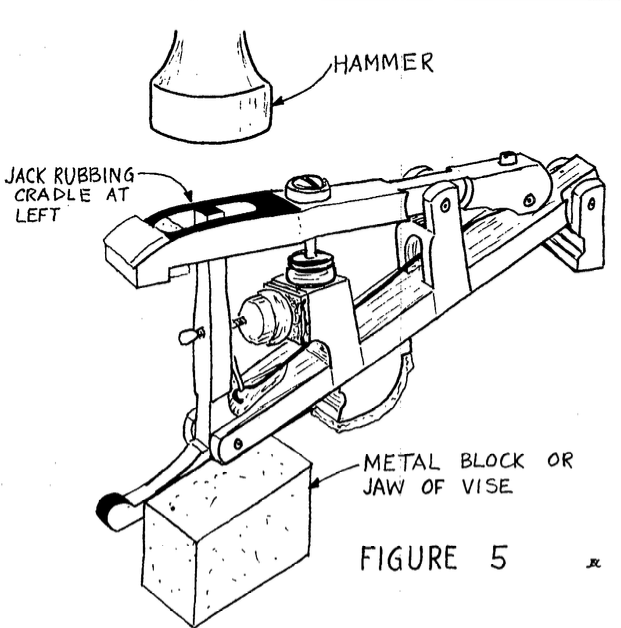

Figure 4, Plate II, shows the action twice its natural size. Since the square piano action functions entirely on the principle of that in Érard grand pianos, the experience of 25 years of manufacturing those was applied to the new one, allowing it to be presented to the public with the utmost confidence. Trials have been made of the same principle's application to upright pianos, and with the same certainty of success, since the principle itself is established irrevocably.

In summary, Érard has introduced their new system of escapement into pianos of different forms, with the same proportion as other makers use simple escapement for pianos of different types. Whether the hammers strike from above or below the plane of the strings, it is the same principle applied to instruments of various shapes and forms. Simple escapement still has its faults, and the double escapement of Érard has its advantages. The long and honorable career of the Érards offers a rare example in the industry of a series of investigations and continual work with perseverance and success.

Few industrial establishments have withstood the test of time for nearly three quarters of a century, making the Érard house a unique example. The important services rendered by Érard to the arts and commerce are admirable, making it a model for all others. From making the first pianos in Paris with their own hands to training able men, the Érards established the division of labor in their workshops, distributing the execution of different parts among different branches of work. They also made and designed the models of the instruments.

Sébastien Érard, a born mechanic, occupied himself with inventions and improvements while his brother watched over manufacture, giving the final perfection to the instrument. Sébastien's spirit of invention was exercised on a plethora of subjects, including the construction of musical instruments, machines, and tools to add precision and speed to facilitate and accelerate the labor of his workers. He filled his workshops in Paris and London with a host of objects that improved many branches of work in general.

In all the branches of mechanics that Sébastien dealt with, he left traces of his genius. He did more for pianos and harps than any other man could have done. The degree of perfection to which he brought the mechanism of the double movement harp and the piano with double escapement leaves nothing to be desired. The Institute affirmed his reputation by expressing themselves thus concerning his talent: “He was among the small number of men who began and finished their art.”

The art of manufacturing musical instruments requires a man of vast conception, for it embraces a number of branches attached to sciences and arts. Sébastien Érard possessed design and mechanical skills, as well as a delicate and experienced ear necessary for harmony and acoustics. He could put his instruments into harmony, tune them, and voice them due to his talent and character, making him a respected figure.

Sébastien Érard, as a founder and inventor, has earned an immortal reputation. With the maturity of piano manufacturing, it is now possible to classify the work into several branches. The first involves conception and invention, the second comprises execution and the division of labor, and the third concerns the choice and use of materials. The Érards have excelled in all of these areas. Later manufacturers have had the advantage of finding the inventions made, the work established, and the choice of materials consecrated by experience.

The Érards trained workers in different branches of piano manufacturing who have since established themselves in the industry and trained others. This has resulted in a division of labor that has given rise to many branches of piano manufacturing in which people specialize in specific areas such as cases, keyboards, and actions. The greater part of piano makers in Paris and the rest of the country only assembles these parts. This division of labor may result in the production of pianos at a good price, but it does not lead to the perfection of the art. To produce perfected instruments, there must be a unity of plan in the direction of the different branches, and the totality must form a perfect whole.

This division of labor also explains how many people, who are not makers, can become such overnight. These new makers are mostly speculators who take advantage of their influence in the musical world as professors or merchants of music to sell instruments made in the manner we just explained. Though such practices can have real disadvantages for the art, they result in improving the lot of the capable workmen who are employed in their factories. Often, these workmen establish themselves as manufacturers in their turn, which has resulted in a growing number of piano makers each day in Paris and the surrounding country.

Competition among speculators, although not always productive for the art, has resulted in the increase of the pursuit of music among the people, providing for a large number of families. The Érards must be proud to think that this important branch of industry, which owes its existence to them, provides for so many families. This is the sweetest recompense for their labors and pains.

Undoubtedly, one of the most critical aspects of piano manufacturing that has not been addressed yet is the procurement of raw materials. The variety of materials used in this craft is infinite, and their preparation adds another layer of complexity to the already intricate fabrication process. Metals, cloth, leather, wood, ivory, and pins are used in an infinite number of forms, and the quality of these materials and the manner of preparing them contribute significantly to the quality of the instrument they are used to produce. In fact, the choice of materials is as crucial as the handwork put into them because good work with subpar materials leads to unsatisfactory results. Among the materials employed, woods require the most meticulous care and attention in their selection and preparation. Experience is the best guide in this matter. To make a good choice among woods, one must have knowledge of the soils that produce them; numerous experiments must be conducted to determine which essential quality is more suitable than another for a specific use. After selecting the woods as logs or planks, the optimal way to cut them must be determined. Furthermore, it is necessary to establish how dry the woods should be before use, and certain woods require three, four, or five years of storage to achieve the desired moisture content. Therefore, in a large-scale factory, a considerable stock of wood is required.

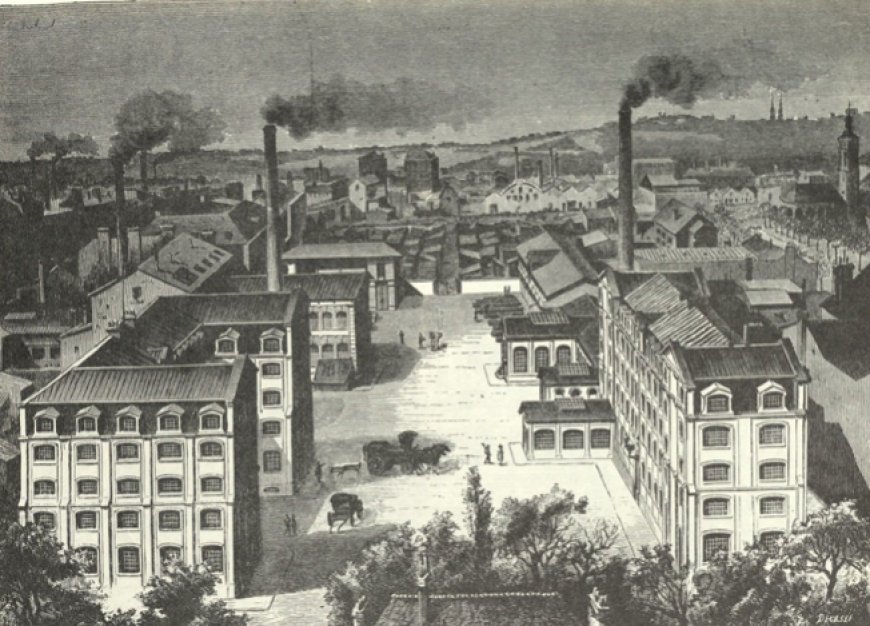

To establish a piano factory that produces high-quality instruments, a host of conditions must be met, including talent, perseverance, and resources. The Érard family has fulfilled all of these conditions to the highest degree. Sébastien, the founder of the establishment, had no equal in his artistry. The family's three generations are a rare example of perseverance. The material resources that have accumulated in Paris and London over the course of more than sixty years are substantial. One must visit the London and Paris establishments, including their branches in the suburbs, to appreciate the scale of the Érards' accomplishments. No other establishment of this kind in Europe has such an imposing whole, and no other competing establishment offers the same level of excellence in the precision of its products.

To appreciate the value of the Érards' merits fully, one must visit their establishment at the industrial product exposition because the means of production reflect the usual level of perfection of a maker's products. The Rue du Mail factory, whose plans and views from different perspectives are attached, covers a surface area of 2,800 square meters in the city's center. It has a calculated surface area of 9,408 square meters, about three acres, including stockrooms, workrooms, sheds, saw rooms, and other spaces. About three hundred workers are employed at the central establishment of Rue du Mail, where everything related to piano production is prepared. Additionally, the Érards have established auxiliary workshops for certain accessory branches, such as rough cabinetry, attached to their extensive lumber yards, situated at rue Saint-Maur-Popincourt, in Paris's highest and airiest quarter.

In sum, when one considers that the factories of the Érards have yielded twenty-five thousand instruments to commerce, of a value of more than fifty million [francs], one can conceive that to wrestle with the need for such material resources, one could only succeeds by forming a stockholding company. But in the arts, what can one expect from a society of speculators? The arts only flourish with independence, and companies of speculators are never more than purely commercial enterprises. Every enterprise, of whatever sort, will always be twenty years behind the new system of Érard in experience; and what it will never have, because it cannot be purchased, is the genius of Sebastien Érard, which shines forth in his inventions.

What's Your Reaction?